Baker Donelson secured a win before the Tennessee Supreme Court when, on February 16, 2024, the Court issued a ruling supporting health care providers and those who seek to secure health care for a loved one. In Williams v. Smyrna Residential, No. M2021-00927-SC-R11-CV (Tenn. Feb. 16, 2024), the Court ruled that when a person chooses an agent they trust to make decisions for them through a General Durable Power of Attorney, that agent may exercise those powers to sign an arbitration agreement when admitting their principal to a long term care community and will not be stripped of that authority simply because they are contracting with a health care provider. Further, the Court held that wrongful death beneficiaries are bound by that arbitration agreement because the decedent's claim, including the agreement to arbitrate that claim, passes to the wrongful death beneficiaries. This is a victory for all Tennesseans who have chosen an agent to make decisions for them and for health care providers who work with those agents to admit individuals needing care into their communities.

The Court ruled that the Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care Act does not strip a General Durable Power of Attorney of the right to choose arbitration as the forum to resolve disputes with a health care provider. Of note, the Court chose not to address the issue of whether a Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care may still sign an arbitration agreement that is provided as an option when securing health care for her principal. The Court reasoned:

To the extent we are leaving questions unanswered, that is because we may only decide the questions that are presented by this case. . . . "We have neither constitutional authority nor inherent power to give advisory opinions" on other issues that are not before us. . . . Chief Justice Kirby's dissenting opinion asserts that it "would be much more practical for the Court to just overrule" Owens [a prior Supreme Court opinion holding that a health care decision maker has the authority to sign arbitration agreements on behalf of their principal] rather than distinguish it. But no party has asked us to overrule Owens, let alone briefed the issue of whether Owens should be overruled. In fact, when asked at oral argument whether the Court should overrule Owens, counsel for defendants insisted that Owens is distinguishable and need not be overruled to resolve this appeal. Deciding whether to overrule a precedent entails consideration of several factors, not simply whether that outcome would be "more practical." . . . Accordingly, that question is best addressed in a case where it is raised by the parties and developed through adversarial presentation. [Citations omitted.]

In declining to address a health care agent's authority to sign an arbitration agreement that is part of the admission process to a long term care community and choosing not to overrule Owens, the Court referenced its holding in that case:

We acknowledged that signing an arbitration agreement is a "legal decision" but rejected as "untenable" an approach that would allow "the attorney-in-fact [to] make one 'legal decision,' contracting for health care services for the principal, but not another, agreeing in the contract to binding arbitration." . . . "Holding that an attorney-in-fact can make some 'legal decisions' but not others," we explained, "would introduce an element of uncertainty into health care contracts signed by attorneys-in-fact" that could make it harder to obtain health care.

Because the Court chose not to overrule Owens, it is logical to infer that the Owens holding – that a health care agent can bind her principal to an arbitration agreement – remains the law. Indeed, as Justice Lee's dissent points out, since not overruled, Owens and its progeny remain the law governing a health care agent's authority to sign an arbitration agreement as part of an admission to a long term care community:

Whether the arbitration agreement in Owens was optional was irrelevant to the issue before the Court – whether a durable power of attorney for health care authorized the attorney-in-fact to sign an arbitration agreement as part of a contract for admission to a nursing home. . . . The decision to admit a person to a health care facility is not a single admission decision; it involves many decisions about living arrangements, services, and numerous other aspects of the person's life. Some directly pertain to health care, and some do not. Similarly, many decisions are not required to be made in a certain way, but they are still required to be made upon admission. The arbitration agreements in Jones, Watson, Bockelman, Mitchell, and Barbee were all optional, yet the court in each case held their execution to be a 'health care decision.' . . . Thus, these Tennessee courts have held that signing an arbitration agreement is a health care decision, even where the arbitration agreement is described as 'separate' or 'stand-alone.' [Citations omitted.]

It seems likely that, given the opportunity, the Tennessee Supreme Court would grant review on a case in which the agent held only a health care power of attorney and signed an optional arbitration agreement. Until then, Owens and its progeny should guide trial courts to find that health care agents maintain the authority to execute both mandatory and optional arbitration agreements with health care providers. When the Tennessee Supreme Court is presented with the case of an optional arbitration agreement signed only by a health care decision maker, the Court could reconcile Williams and Owens by recognizing that the decision to sign an arbitration agreement as part of admission to a long term care community necessarily involves legal and health care decisions and falls within the authority of both a legal decision maker and a health care decision maker (as opposed to one or the other). That result would be consistent with its rulings and reasoning in Williams and Owens and would prevent the "untenable result" warned against in Owens. It would give clarity to those seeking to admit loved ones to long term care communities, and to health care providers attempting to help those agents secure much needed health care for their loved ones. That said, the majority's opinion in Williams makes clear that the Court will closely examine the specific language of any power of attorney that it is reviewing. And while the Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care Act states that only an authorized attorney-in-fact for health care may make a "health care decision" as defined under that act, the Tennessee Uniform Durable Power of Attorney Act does not have the same restriction. Thus, it is logical that a health care attorney-in-fact could have the authority to enter into an optional arbitration agreement with a health care facility under the terms of an otherwise valid power of attorney for health care.

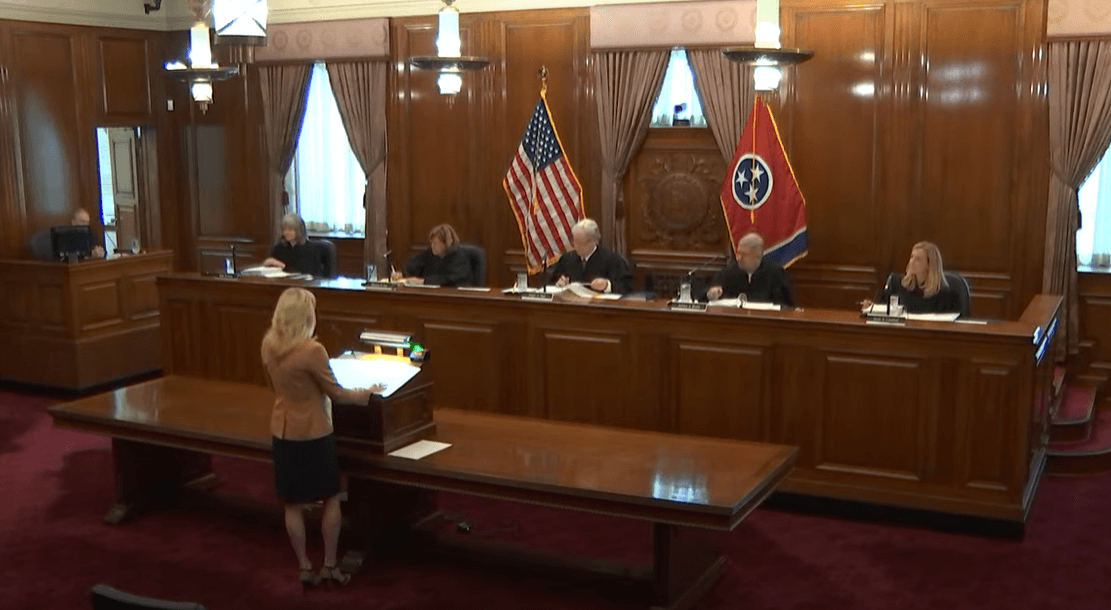

(Source: TNCourts)

Christy Tosh Crider, who chairs the Firm's Health Care Litigation group and Baker Women, its women's initiative, along with Shareholder Caldwell G. Collins and Associate W. Preston Battle IV, led the appeal on behalf of Smyrna Residential. A link to the opinions are here. A link to the oral argument is here.

Should you have any questions about this decision, please contact Christy Tosh Crider.