The ever-increasing cost of disasters and Congress' reliance on 11th-hour continuing resolutions (CRs) often result in a storm of questions regarding disaster appropriations. This disaster recovery brief explains some of the Federal Emergency Management Agency's (FEMA) many different funds and authorities, how Congress funds them, and how that funding directly affects the public.

Response, Recovery, and Mitigation Grants

The Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, as amended (Stafford Act), authorizes FEMA to use funds appropriated into the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) to provide grants for response, recovery, and mitigation including the Public Assistance (PA) Program, Individual Assistance (IA) Program, Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP), the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program, and others.

Although the DRF regularly receives funding through the annual appropriation process each year, it is also funded through supplemental appropriations, which Congress provides in response to particularly large events. The DRF is a "no-year fund," meaning that when Congress appropriates money into this fund, it is available until expended. Money in the DRF does not become unavailable at the end of the federal fiscal year. Because of this, activities funded by the DRF can continue even if there is a federal government shutdown. Only FEMA's internal operations, which are funded by annual appropriations, must pause (more on this below).

In the FY 2024 budget, Congress appropriated $20.26 billion for the DRF. Unfortunately, a steady increase in disaster costs made that amount insufficient to meet FEMA's needs this year. In the decade between 2010 and 2019, the United States sustained 131 weather and climate disasters where overall damages reached or exceeded $1 billion, adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to 2024. That is an average of 13 per year. Meanwhile, in 2023 alone, this country experienced 28 "billion-dollar events," and as of September 10, 2024, we have already experienced 20 such events. The term "billion-dollar event" refers to events with damages that exceed $1 billion. It does not mean that the damages totaled $1 billion or that the total cost of recovery was only $1 billion. In reality, costs far exceed $1 billion for each such event. With higher disaster costs, there is a greater reliance on federal disaster funding and an increased spend from the DRF. An appropriation of $20.26 billion simply does not go as far as it once did. This year, as has happened more often in recent years, the DRF balance ran low as we entered peak hurricane season and FEMA implemented what it calls Immediate Needs Funding (INF) procedures to avoid exhausting all available funds in the DRF.

Under INF procedures, FEMA paused all obligations that are not for lifesaving, life-sustaining, or critical ongoing disaster operations. This means that new obligations for BRIC grants were paused so that the funds could be used to fund emergency activities. It also means that PA permanent work projects, COVID-19 emergency work projects, and HMGP projects continued through the agency's review process but stopped before obligation. Just like the BRIC awardees, none of those PA permanent work, COVID-19 emergency work, or HMGP projects will be paid until the DRF is "sufficiently replenished" such that FEMA is comfortable that it can resume those obligations without exhausting the balance of the DRF and jeopardizing its lifesaving operations.

INF procedures did not affect emergency work funded by the PA Program, or assistance to individuals and households under the IA Program. The balance of the DRF has never been allowed to reach zero, and one hopes it never will.

The DRF can be "sufficiently replenished" through a full-year budget, a supplemental appropriation, or a CR. A CR is a stop-gap measure that buys Congress more time by extending funding levels on existing programs from the prior fiscal year if they can't reach an agreement on a budget by the end of the fiscal year (midnight September 30 each year). Typically, CRs extend funding levels without change and authorize the executive branch to give agencies only the amount of funding necessary to reach the expiration date of the CR. They've lasted as little as one day and as long as the rest of the fiscal year (i.e. a full-year CR). However, since FY 2018, CRs typically include what is called an "anomaly" for the DRF that allows funds to be apportioned to FEMA at a rate to cover response and recovery activities under the Stafford Act. This anomaly allows the CR to act as a full-year budget with regard to the DRF. So, even in the event of a one-day CR, with the anomaly, the DRF can receive the full amount appropriated for the DRF the prior year, "sufficiently replenishing" the fund so that FEMA can lift INF restrictions and resume obligating funds.

FEMA's Annual Appropriation

The agency's own internal operations are not funded by the DRF. Instead, they are funded annually, through the Department of Homeland Security's appropriated budget. Those funds, which are used to pay for FEMA facilities, permanent full-time employees, non-disaster contracting, and other such activities, expire at midnight on September 30 every year.

The Antideficiency Act prohibits the federal government from obligating itself to pay expenses above its available resources. This is why, if there is no Homeland Security budget or CR passed before the end of the current fiscal year, FEMA would need to shut down with the other unfunded federal departments and agencies. However, the Antideficiency Act has some exceptions, one of which is that employees necessary to protect life and property are exempted. This means that exempted employees can be required to continue performing their job functions throughout a shutdown, without pay. Some of FEMA's workforce falls within that category. All other activities normally funded by FEMA's annual appropriation would cease.

Occasionally, the federal government ( FEMA included) has shut down while disaster operations funded by the remaining no-year balance of the DRF, continued. In those instances, although actions necessary to protect life and property continued, the agency's operational efficiency was impacted, and some activities could not be performed because they relied upon unfunded personnel or contracts.

Preparedness Grants

Every year, FEMA is also appropriated funds for the award of preparedness grants including the Assistance to Firefighters Grant Program, the Emergency Management Performance Grant, the Homeland Security Grant Program, the Port Security Grant Program, the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program, and many others. Like the agency's annual appropriations, funds appropriated for those programs expire at the end of the fiscal year, and FEMA routinely obligates them before then. If Congress does not appropriate funds for these programs in any given year, they will not be provided to the public. If Congress simply fails to timely appropriate funds for these programs, resulting in a government shutdown, it would just delay the publication of funding opportunity notices that would be issued by the agency once Congress eventually appropriates the funds.

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP)

FEMA operates the NFIP under the authority of the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968, as amended, which requires periodic action by Congress to authorize FEMA to continue to provide flood insurance and other related services including flood mapping. Since the NFIP authority expired in 2017, the program has been through at least 25 short-term extensions, including three brief lapses. During the lapses, FEMA and Congress never failed to honor the flood insurance contracts that were in place before the lapse. Also, even during a lapse, FEMA would still have the authority to ensure the payment of valid claims with available funds, unless the National Flood Insurance Fund runs out of money.

During a lapse, however, FEMA immediately stops selling new policies and renewing policies for millions of properties in communities across the nation. Because flood insurance is required for some federal housing, mortgage, and other funding programs, the impact on FEMA's inability to sell or renew flood insurance policies would impact thousands of real estate transactions.

Conclusion

As we again approach the end of the federal fiscal year with FEMA in INF status, and Hurricane Helene making landfall, communities around the country are anxiously watching and wondering if the assistance they need to recover from a disaster will be available. Importantly, the FY 2025 CR includes what has wisely become a now-standard anomaly provision that allows the temporary budget authority for the DRF to "be apportioned at a rate for operations necessary to carry out response and recovery activities under the Stafford Act." With this language in the law, there should be funds available in the DRF necessary to carry out response and recovery operations pursuant to the Stafford Act, which should allow FEMA to lift INF procedures. The FY 2025 CR also includes language that would extend the NFIP and fund the National Flood Insurance Fund.

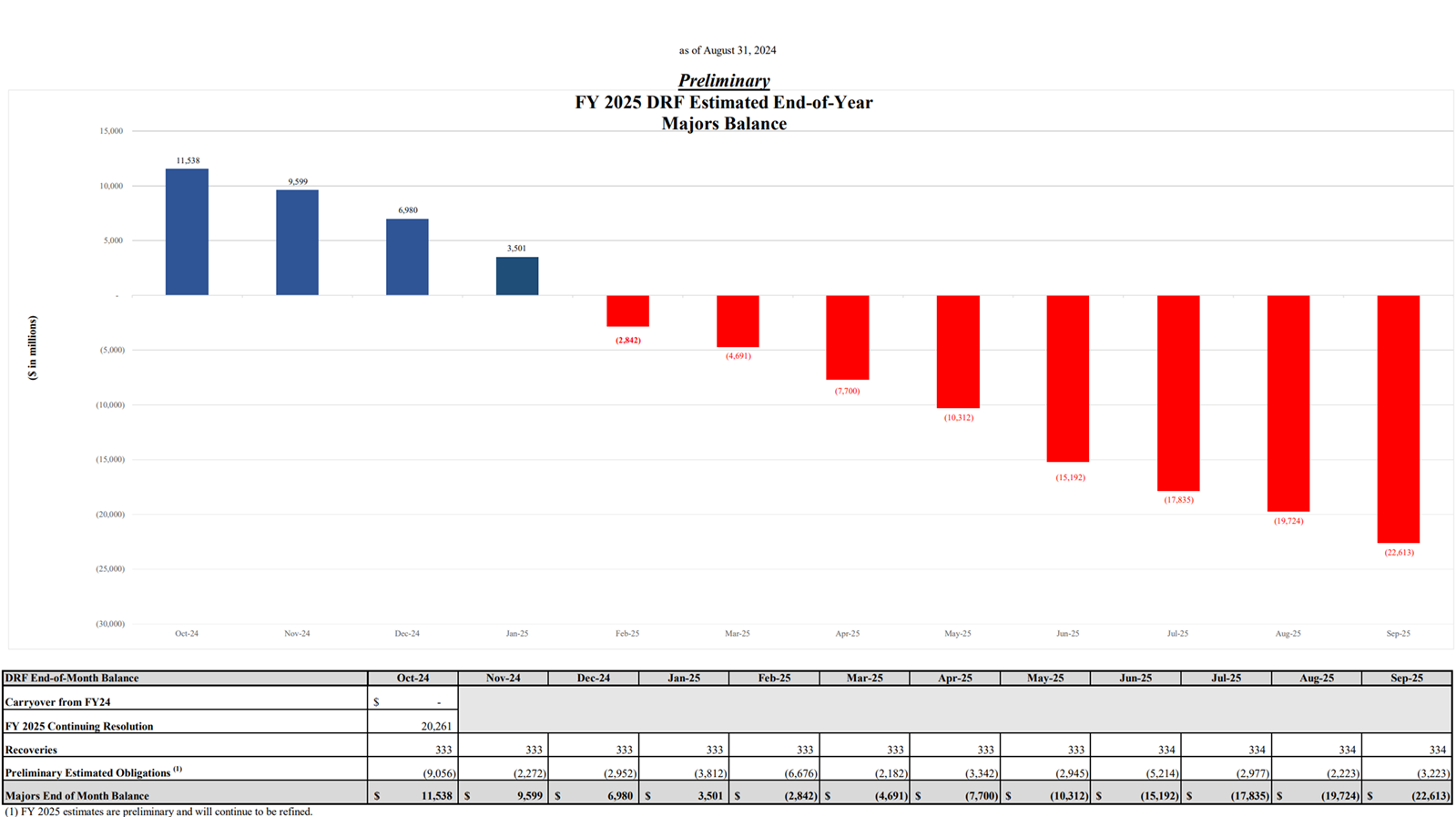

But this is a temporary fix. Even with the CR, FEMA projects it will exhaust available funds, and go into a $2.8 billion deficit as early as February, 2025.

Without a sizeable supplemental, it is likely that the agency will need to reinstate INF procedures again soon. When FEMA implemented INF procedures on August 7, 2024, the DRF Majors balance was approximately $3 billion, with a projected $6 billion deficit by the end of September. Presuming it continues to apply similar triggers, it is likely that FEMA will need to institute INF procedures again around the same time that the CR expires (December 20, 2024).

If you have questions about FEMA funding and programs please contact Erin Greten or any member of Baker Donelson's Disaster Recovery and Government Services team. If you have questions about the appropriations process or any particular piece of pending or desired legislation, please contact Sheila Burke or any member of Baker Donelson's Government Relations and Public Policy team.